The Bright Key and the Leaky Ship: A Franklinist Guide to Evaluating Corporate Efficiency (and Folly)

Insights from "The Way to Wealth" for better investing

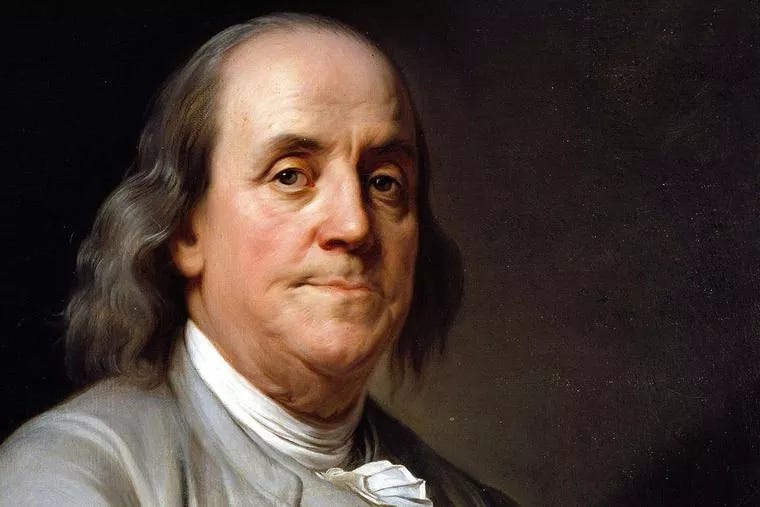

If you were walking through the streets of Philadelphia in the 1730s, you might have come across a curious sight: a man of growing international renown (a scientist, inventor, and publisher) personally pushing a wheelbarrow laden with paper and supplies through the city’s cobblestone streets.

No, this wasn’t a performance born of necessity; Benjamin Franklin was already a man of means. It was, instead, a calculated display of virtue. Franklin, understood that a reputation for diligence was as valuable a business asset as the printing press itself. He was ensuring everyone knew he was working hard, demonstrating the practical, sleeves-rolled-up ethos he preached.

Now, can this 18th-century philosophy of relentless work and careful spending (what Franklin called “industry and frugality”) become a tool for analyzing companies today? Can we, in essence, find the ghost of Franklin’s diligence in a company’s return on invested capital, or the echo of his frugality in its selling, general, and administrative expenses?

Well, as investors, our task is to to discern whether a company’s proclaimed “culture of efficiency” is merely a performance, a PR-crafted wheelbarrow pushed for show, or if it is the genuine, value-creating engine of the business.

In today’s article, I’ll look for insights in one of Franklin’s seminal works: The Way to Wealth1.

The Twin Pillars of Corporate Character

Benjamin Franklin’s The Way to Wealth is, at its heart, a treatise on character.

He argued that wealth was not a matter of luck or genius, but the natural outcome of two core virtues: Industry and Frugality.

For us investors, I’d say that these twin pillars are the mark of a durable corporate culture that generates superior, long-term returns.

A company that is truly “industrious” is one that deploys its capital and labor with intense, focused purpose. A company that is truly “frugal” is one that stewards its resources with disciplined care, waging a constant war against waste.

Together, they form a powerful lens for separating well-managed, efficient enterprises from their bloated, unfocused, and often doomed competitors.

"Plough Deep While Sluggards Sleep": The Mechanics of Relentless Execution

Franklin’s didn’t refer to industry as just being busy of course. He meant the productive and purposeful application of effort.

“Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labor wears, while the used key is always bright,” he wrote, showing this idea that idleness is an active corrosive force. His advice to “drive thy business, let not that drive thee” was a call for proactive, intentional management rather than reactive crisis-handling.

Now, in modern corporate terms, this virtue could very well be the essence of operational excellence and efficient capital allocation.

So which key financial metrics would point us in the right direction to asses this Franklinist notion of industry?

The first that comes to mind is Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). In simple terms, ROIC measures how much profit a company generates for every dollar of capital, both debt and equity, invested in the business. A company with a consistently high ROIC is, by definition, “doing to the purpose.”

A second, related metric could be Asset Turnover, which measures how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate revenue. A high asset turnover ratio suggests a business is using its assets, keeping the key bright through constant use rather than letting it rust.

We could go as far as to borrow a concept from physics: the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Yes, the concept of entropy, that idea that describes the universe’s tendency to go from order into disorder.

A tidy room, left alone, becomes messy. A hot cup of coffee cools to room temperature. Order is artificial and requires a constant input of energy to maintain; chaos is the natural default state.

A company is no different. Left to its own devices, it will inevitably succumb to organizational entropy: bureaucracy accumulates, communication breaks down, processes become inefficient, and well, complacency sets in. “Industry,” in this view, is the intelligent, focused energy that management must constantly apply to fight this natural decay.

This lens reveals the fatal flaw in many large, complex organizations. As a company grows, its internal complexity (the number of people, processes, and divisions) increases. This dramatically increases the potential for disorder, meaning the energy required to maintain order and efficiency grows exponentially.

The growing, disconnected business units create immense internal friction and a stifling bureaucracy that restrains management’s ability to create value. Few are the exceptional companies that manage to escape this fortune.

Now, this insight begs the question: is the management team a force for order, or merely stewards of decay in those type of situations?

Perhaps we can find some light in the following short video:

"Beware of Little Expenses": The Psychology of Corporate Frugality

If industry is about the productive use of capital, then frugality is about the disciplined preservation of it. For Franklin, this was about a rational aversion to waste born of "pride" and "folly".

His famous aphorism, “a small leak will sink a great ship,” is a timeless warning about the corrosive power of unchecked costs.

He also observed that “pride is as loud a beggar as Want, and a great deal more saucy.” Isn’t that the perfect description of much corporate waste, driven not by operational necessity, but by ego and the desire for status?

Now again, which key financial metrics would enlighten us to assess frugality?

Perhaps the clearest signal of a frugal or profligate culture is the line item for Selling, General, and Administrative (SG&A) expenses. As we know, this figure represents a company’s overhead (the cost of its headquarters, corporate salaries, marketing, and other non-production expenses).

When measured as a percentage of revenue, SG&A can reveal how much a company spends just to keep the lights on. A low and tightly controlled SG&A ratio could be the hallmark of a frugal culture.2 This discipline would typically translate into a healthy and stable Operating Margin.

The modern master of Franklinist frugality is undoubtedly Costco (COST). The company’s entire business model is an exercise in disciplined cost control. Its warehouses are spartan, with goods stacked on industrial pallets. It carries a radically limited number of products (around 4,000 SKUs, compared to over 100,000 at a typical Walmart), which maximizes its purchasing power with suppliers.3 Most famously, Costco spends next to nothing on advertising, saving an estimated 2% of costs annually and relying on word-of-mouth and member loyalty.

This discipline is enforced by a strict, self-imposed cap on gross margins (14% on outside brands and 15% on its own Kirkland Signature products) ensuring that cost savings are passed directly to the customer.4 This culture of thrift results in an SG&A-to-revenue ratio of around 9-10%, remarkably low for a retailer. This is definitely not a company that allows small leaks.

Invert, always invert. So which company best illustrates the definition of corporate profligacy?

Well, WeWork provides an almost cartoonish example of an anti-Franklinist culture. The CEO’s personal use of a $60 million private jet, ill-advised corporate investments in unrelated businesses like an artificial wave pool company, and a business model where losses grew in lockstep with revenues. In 2018, the company posted a staggering $1.9 billion loss on $1.82 billion in revenue. What’s more, its balance sheet was burdened with some $47 billion in long-term lease obligations, a flagrant violation of Franklin’s warnings against the slavery of debt.5 This was a ship full of leaks, captained by pride and folly.

Albeit probably unnecessary, let’s place both examples side by side.

These are notably the two extremes and as with all things in life, there’s nuance to this idea. A purely ascetic view of frugality can be misleading. Franklin himself noted, “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest”. The key is to distinguish between wasteful spending and strategic investment.

The Franklinist investor, therefore, doesn’t just look at the size of the expense. They analyze the return on that expense, for each and every meaningful expense. True frugality is the ruthless elimination of unproductive costs; waste, vanity, and bureaucratic bloat, not the myopic avoidance of strategic investments that fuel future growth.

The Enduring Signal

Let us return, one last time, to the image of Franklin and his wheelbarrow, which represents an obsession with the tangible, the necessary, and the productive. It is the ethos of a leader focused on the core task of moving the "paper" (running the business) rather than indulging in the "finery" of a lavish headquarters, a corporate jet, or a value-destroying acquisition. The wheelbarrow is a declaration of priorities: substance over status, efficiency over ego.

You can still spot this signal, if you know where to look. When Constellation Software’s Mark Leonard famously flew coach, it wasn’t because the firm couldn’t afford business class. It was a deliberate cultural message. A form of capital allocation theater. Leonard understood, like Franklin did, that leadership by example can encode values more durably than any corporate memo. Frugality at the top becomes frugality throughout.

Hopefully, I’ve shown that the timeless virtues of industry and frugality provide a powerful and durable framework for identifying businesses with deep operational moats and superior capital discipline.

It’s the wheelbarrow, airborne.

Disclaimer

This newsletter (the “Publication”) is provided solely for informational and educational purposes and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security or other financial instrument, nor should it be interpreted as legal, tax, accounting, or investment advice. Readers should perform their own independent research and consult with qualified professionals before making any financial decisions. The information herein is derived from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed to be accurate, complete, or current, and it may be subject to change without notice. Any forward-looking statements or projections are inherently uncertain and may differ materially from actual results due to various risks and uncertainties. Investing involves significant risk, including the potential loss of principal, and past performance is not indicative of future results. The author(s) may hold or acquire positions in the securities or instruments discussed and may buy or sell such positions at any time without notice. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are subject to change without notice. Neither the author(s) nor the publisher, affiliates, directors, officers, employees, or agents shall be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising from the use of, or reliance on, this Publication.

Harvard Business School scholars and historians credit it with helping to shape early American capitalism through its enduring aphorisms; phrases like “Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise,” and “There are no gains without pains”; that remain embedded in popular culture.

Suffice it to say that SG&A ratios should always be evaluated in the context of industry peers, as cost structures vary widely across sectors. What qualifies as “lean” in one industry might be excessive in another.

Decency Means More than “Always Low Prices”: A Comparison of ..., accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ou.edu/russell/UGcomp/Cascio.pdf

Decency Means More than “Always Low Prices”: A Comparison of ..., accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ou.edu/russell/UGcomp/Cascio.pdf

Why WeWork Won't - Harvard Business School, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/Final%20Version%20WeWork%20Article%20HBS%20Header_91efe3b9-fc0b-408b-b29e-d7d365a245b2_f7f6a0fa-cf26-4caa-99cc-3653fc8e6dc6.pdf