On Why Carrying a Notebook Might Make You a Better Investor

Exploring how history’s greatest minds leveraged constant note-taking to unlock extraordinary insights—and how you can too

I have an old-fashioned belief that I only should expect to make money in things that I understand. I don’t mean understand what the product does. I mean understand what the economics of the business are likely to look like ten years from now.1

-Warren Buffett

It is said Buffett invested in Apple after observing his grandchildren and realizing how “sticky” the use of the phone and its apps was. This simple insight would go on to generate tens of billions of dollars for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders over the following years.

Now, not everyone has Buffett’s mind. But can we, mere mortals, improve our chances of generating similar insights about a company? Are there protocols we can apply during analysis that lead to a deeper understanding of the dynamics at play?

What if there were a technique that systematically improved both the quantity and quality of your business insights? It could give you an edge over the market—an analytical edge.

I’ll dig into that shortly, but first, let’s take a quick detour.

A Lineage of Genius Note-takers

One chilly afternoon in 1820, a solitary composer walked through the woods outside Vienna. Ludwig van Beethoven paused beneath some trees, ears listening to birdsong. Pulling a small notebook from his coat pocket, he scribbled a few musical notes before the melody could escape. This was nothing less that the seed of a symphony.

Beethoven always carried a notebook on his long nature walks, ready to catch inspiration the instant it struck. In fact, many of history’s lesser-known creative geniuses shared this habit. From scientists to poets, they tucked journals into their pockets and filled them with fleeting ideas, sketches, and observations.

Over time, these private pages became incubators for world-changing creativity—a virtuous cycle where jotting down one insight sparked the next.

Journaling his musical thoughts allowed Beethoven to return to them, twist them in new directions, and polish them to brilliance.

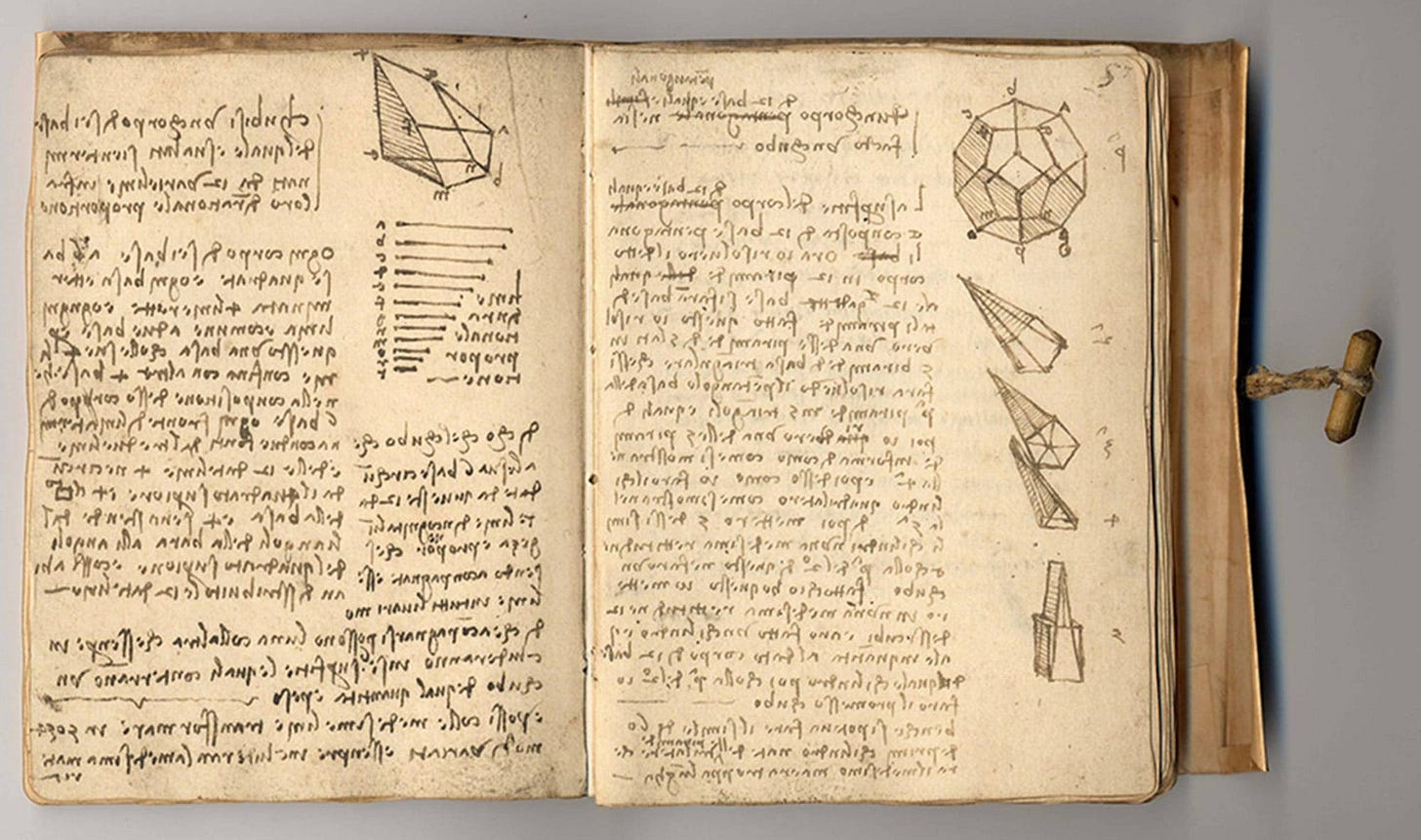

Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the greatest polymath of all time, famously kept small, belt-tied notebooks to jot down ideas, sketches, and observations as they arose. His larger journals—spanning over 13,000 pages—contain intricate drawings and reflections from daily life, such as the movement of water or the curl of a strand of hair, which he would later refine from memory.

Or take the case of a curious young French aristocrat who set sail for America with a notebook always in hand.

This Frenchman spent nine months crisscrossing the United States by steamboat, stagecoach, and horseback, jotting incessantly in his travel diary about everything he saw. Nothing escaped his pen: the rough-and-tumble debates in frontier taverns, the piety of New England churchgoers, even the spectacle of a backwoodsman-turned-politician. The very act of keeping a journal became a tool of analysis.

He would reread earlier entries, turning disparate anecdotes into patterns in his mind. When he returned to France, he spread his voluminous notebooks and bundles of notes across his desk and began distilling them into a masterpiece. This young Frenchman was Alexis de Tocqueville, and the result of his furious note-taking habit was Democracy in America—one of the most insightful works of political philosophy ever written.

Tocqueville’s habit of writing everything down had created a virtuous cycle: daily note-taking sharpened his insights on the fly, and later, those raw notes could be mined, compared, and refined into lasting ideas.

And how could I forget Benjamin Franklin—Munger’s hero—who famously used notebooks to capture his daily insights, ideas, and observations.

You see this pattern again and again—great minds writing daily, often frantically, to capture the insights that struck them throughout the day.

The act of journaling, as these figures show us, can create a virtuous cycle: observation leads to notation; notation leads to reflection; reflection leads to deeper observation – and so on.

By now, you may be wondering: was the act of writing down their ideas a cause of their genius, or merely a consequence of it?

Win Wenger, Ph.D.—a pioneer in the fields of creativity and learning—argued it was the former.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Wenger conducted fascinating research on how the subconscious mind can be harnessed to boost creativity and intelligence.

So, if this habit was indeed a driver of genius throughout history, is there a way we can apply its principles to sharpen our business analysis skills?

You Are Brighter Than You Think

Wenger suggests that we all start with roughly the same “brain equipment.” The difference isn’t raw intelligence—it’s that a few individuals, often by chance, stumble into novel ways of thinking, seeing, or approaching problems.

These small early differences compound over time, leading to outsized results. What we eventually label as “genius” often begins as nothing more than a slight deviation in perspective or method—amplified day after day through consistent practice and feedback.

Take the case of Richard Feynman. As a young student, he developed the habit of explaining complex ideas in his own words using simple analogies—what we now call the Feynman Technique. This self-taught strategy helped him build a deeper understanding of physics than many of his peers, setting the foundation for the breakthroughs that would later define his career. What started as a quirk of study habit became a superpower.

This same principle applies to the behaviour of noticing things in you own peripheral awareness.

How many times have you had an idea or a truly original insight, only to let it slip away—never telling anyone, never even writing it down?

“Most men stumble over great discoveries. – But most, then pick themselves up and walk away!”

-Winston Churchill

Think Deeper, Learn Faster

Considering all this, the techniques I’m about to share are grounded in just three simple psychological principles. That’s it—three core principles to help you generate deeper, sharper insights:

Principle 1: You get more of what you reinforce.

Also known as the Law of Effect, this principle suggests that behaviors or patterns of thinking you reward or repeat tend to strengthen over time. The more you reinforce a certain kind of observation or inquiry, the more naturally it will emerge in the future.

Principle 2: Describing your perceptions aloud reveals more.

What you describe aloud to an external focus while you’re examining it—using your own direct perception—will deepen your understanding. This is essentially the Socratic method in action. Socrates structured his dialogues so students had to articulate a problem aloud, often in front of others. The very act of describing their perceptions triggered new insights. Speaking to an external focus reinforces your attention on the object of study, helping you see more of it.

Principle 3: Increase neurological contact with what you want to learn.

We often say, “If I could just get a handle on this…” But what we really mean is: “If I could increase my brain’s engagement with this concept.” Wenger (1992)2 offers a memorable analogy:

Try lifting a chair with just your pinky finger. It’s possible, but extremely difficult. Now try using your whole hand and both arms. Much easier, right? Same idea. Most people are taught to learn by direction and example, using only a small fraction of their cognitive capacity. True learning happens when you bring your full neurological resources to the task.

To summarize, the techniques below are built on these three principles:

You get more of what you reinforce.

What you describe aloud to an external focus while perceiving it leads to deeper insight.

Increasing neurological contact boosts learning and retention.

Each of the techniques that follows is designed to activate all three. So—what are they?

The Portable Memory Bank

The first technique proposed by Wenger is simple—and I almost hinted at it in the geniuses across history section. It’s called the Portable Memory Bank.

Imagine carrying a vault of your most valuable insights, observations, and half-formed ideas—accessible anytime, anywhere. That’s the essence of The Portable Memory Bank. A pocket-sized notebook.

Just carry around a notebook and capture thoughts the moment they arise—no matter how incomplete or strange they seem. Insights fade fast, but if recorded, they compound. You have to reinforce the behaviour of having original ideas, and writing them down does exactly that.

Over time, you’ll start seeing patterns, themes, original insight start to emerge. What feels like a random note today could become the seed of your next big insight tomorrow.

Now, let’s talk about the second technique proposed by Wenger, which builds on top of the Portable Memory Bank.

Writing to Understand: A Method for Better Learning

Wenger called this, The Freenoting Technique. I’d say is something akin to brainstorming on paper.

To start freenoting follow this simple method:

Begin reading something of interest to you (could be an annual report), and every page or two, pause. Have a notepad or a laptop ready, and start writing—fast.

Jot down everything that comes to mind: perceptions, reactions, questions, objections, counterarguments, even seemingly unrelated thoughts. The key is not to stop and evaluate whether something is worth writing. You’re clearing the creative pipe, making room for deeper insights to flow. Think of it like Julian Shapiro’s idea of creativity as a clogged faucet, or as Ed Sheeran once described: you need to let the dirty water run before the clean water can come through.

Try starting with your immediate perceptions of the topic at hand, but don’t worry if your mind drifts off-topic. Keep writing. Each thought you record becomes a handle with which your brain can grasp and revisit what you're trying to learn.

After a few minutes of this furious scribbling, pause and reflect: Did you uncover insights that were later echoed in the book or lecture? Did new connections emerge?

The goal here is to bypass the inner editor of your conscious mind and tap into your subconscious creativity.

Have you ever been in a meeting where you're so focused on something you want to say that it becomes hard to pay attention to what's being said? The same principle applies here: your unconscious mind wants to be heard. Let it speak.

Importantly, write down your perceptions in as much sensory detail as possible. This activates all three psychological principles we’ve discussed:

You get more of what you reinforce.

Describing your perceptions aloud (or in writing) reveals more of the subject.

The act of writing increases neurological contact with what you're learning.

The golden rule: never stop to decide whether a thought is “worth” writing. If it occurred to you, it’s worth recording. You can evaluate later.

It’s like the famous Feynman anecdote: a journalist once visited his office and, seeing shelves of notebooks, remarked, “It’s incredible to have a record of all your thoughts.” Feynman quickly replied, “They’re not a record of my thinking—they are my thinking.”

Feynman wasn’t documenting ideas, he was thinking on the page—exactly what freenoting demands of you.

You won’t know if most ideas are good or bad until you finish writing them. So if one pops into your mind, get it down.

All learning is a creative act. Without creation, there is no real learning. What makes for good creation makes for good learning.

To nourish the mind, information must be transformed—then re-transformed, and re-transformed again.

Final Thoughts

So remember—next time you’re trying to understand something difficult or complex, just start jotting down your thoughts without pausing to judge whether they’re “correct.” By doing this, you’ll be reinforcing your creative instincts, uncovering more of what you’re analyzing, and increasing your neurological contact with the subject at hand.

When you recognize that you’ve had an idea, don’t let it slip away. Write it down. Record it. Share it. The very act of capturing your observation reinforces the habit of being perceptive—and who knows, you might just stumble upon your next great investing idea.

Disclaimer

This newsletter (the “Publication”) is provided solely for informational and educational purposes and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security or other financial instrument, nor should it be interpreted as legal, tax, accounting, or investment advice. Readers should perform their own independent research and consult with qualified professionals before making any financial decisions. The information herein is derived from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed to be accurate, complete, or current, and it may be subject to change without notice. Any forward-looking statements or projections are inherently uncertain and may differ materially from actual results due to various risks and uncertainties. Investing involves significant risk, including the potential loss of principal, and past performance is not indicative of future results. The author(s) may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed. Neither the author(s) nor the publisher, affiliates, directors, officers, employees, or agents shall be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising from the use of, or reliance on, this Publication.

Buffett, W. E. (2001). Speech at the University of Georgia [Transcript]

Wenger, W. (1992). Beyond teaching & learning. Project Renaissance.

I could not agree with this more. I have been a compulsive pen-and-paper note-taker my whole life, and while I've watched others and made attempts myself to take notes on laptops or other electronic devices, I always reverted to chronological paper notebooks.

Interestingly, pretty much everything I take notes on ends up later in some electronic form (anaylst research, Facebook diary posts, Substack pieces, Excel spreadsheets, etc.), so between those and my Google calendar, I can usually search out the date I took the notes and direct myself to the original pages. I did jettison almost 40 years of work-related notebooks when I retired (too much to store, needed to go to the shredder for legal reasons), but the important content had been already transcribed, and I still have everything from college and high school, as well as my retired years. I also have some small notebooks in my fishing and shooting bags, as well as ones in my classic cars to jot both minutiae (that dry fly your guide suggested that caught a lot of fish, a kind of ammunition that was especially effective, etc.) impressions as they happen.

People remark that I have a photographic memory. I don't, but can find everything in my notebooks in minutes. I also find the physical act of writing serves as a great memory-reinforcer.

When I see someone *not* taking notes, who invariably say that they're remembering everything (sort of akin to how people who say "breakfast is the most important meeting of the day" are usually fat), I view it as insulting. I once had a boss who reprimanded me "why are you always taking notes?". I never thought of him the same way after that.

By the way, every time I see Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks (pages of which I viewed in person at the Queen's Gallery in London), I always think of Doug Kenney's March 1971 parody, pp. 31-35 of this https://1drv.ms/b/c/5ed4c22a9f7768df/Ed9od58qwtQggF5I8AIAAAAB78DECCPviW2G3HuhIuOM4Q . Along with French artist Daniel Maffia, Kenney shows us the "Hulus Hoopus" that can be used to alleviate "Eccesso Obesito Del Gross Stomacchi", a rolling mousetrap on wheels, Batman's bat signal, "Una Volante Pizza"), and a heart-transplant procedure involving "mio cane Fido" or "mio stupido e gullibilio assistante Mario" as the donor.

Fascinating read!